Chromium: Same Origin Policy bypass within a single site a.k.a. "Google Roulette"

Suppose you’re visiting a legit website, like developers.google.com, which tells you to open a JavaScript console in your browser, and then just invoke a function called magic(). Would you do it?

Of course, the function may access everything within the scope of https://developers.google.com but it cannot steal data from other origins. Or can it?

In this post, I’m describing a security issue in Chromium, which proves that entering code in a JavaScript console can have a little broader consequences than it may initially seem.

A little background

The issue in question is Chromium bug #1069486 that I reported back in April 2020.

As of 16th November 2022, the bug is not fixed, which essentially makes it a 0-day. However, I got explicit permission from the Chromium team to do a full disclosure. Also, because the attack scenario requires the victim to enter code in the DevTools console, I believe it’s not practically exploitable.

I still think that there might be some ways to escalate it that I failed to discover, and maybe you, my dear readers, will have some better ideas.

JavaScript console and utilities

But let’s start with some basics. When you enter code in the JavaScript console, it should be equivalent to executing the same code directly by the website. This means, among others, that even in the console you cannot bypass Same-Origin-Policy or other fundamental security principles imposed by browsers.

The truth is, however, that the console is a little bit more powerful than the “normal” JavaScript. The difference lies in console utilities. These are a bunch of functions that are exposed only to the console and they are not available from “normal” Javascript. Let’s see what it means.

As an example, take a function called $$. This is a shorthand for document.querySelectorAll, available only in the console.

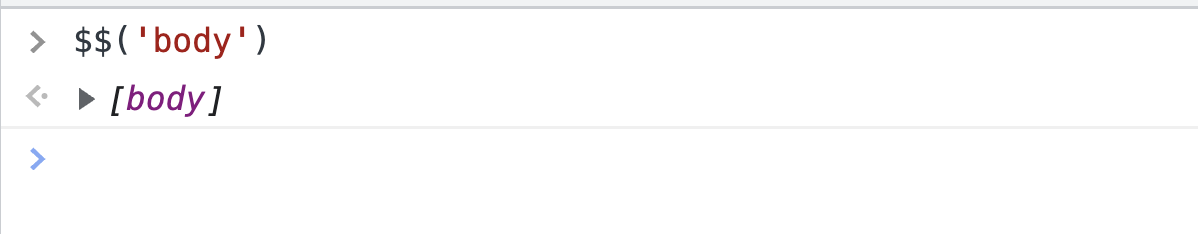

If you try to call it from the console, the function executes just fine:

On the other hand, if you try to call it directly from your HTML, such as from the following code:

<script>

$$("body");

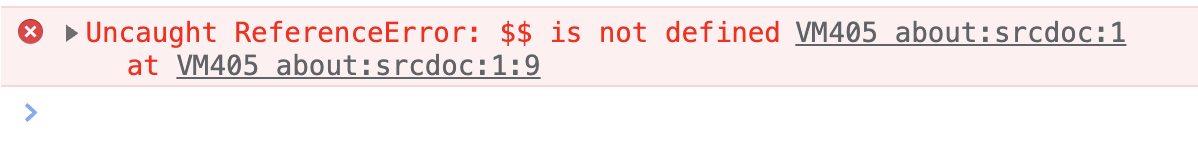

</script>Then you’ll get a ReferenceError:

I consider this an expected behavior. Now we may conclude that Chromium must differentiate whether a JS code was executed from the console or not and decide whether utility functions should be exposed to the code.

At this point, I wondered how exactly Chromium tracks the source of the function call. So my idea was to create a <script> tag containing a reference to $$ and see what happens when we call the function from the console.

So I created an HTML file with the following snippet:

<script>

function magic() {

console.log($$);

}

</script>Afterward, I tried to call magic() from the console. I could’ve imagined Chromium reacting in one of the two following ways:

- Return a reference to the console utility

$$as the code is ultimately invoked from the console. - Or throw a

ReferenceErrorsince the reference to$$is in “normal” JavaScript.

This proves that “normal” JavaScript code can contain references to console utilities, and they will be executed if you call them from the console.

So this brings us back to the scenario mentioned at the very beginning of this post: we’re visiting a malicious website that asks us to execute something simple in the console. Now the question is: can console utilities do something evil?

The answer is: yes, they can! And to prove it, I’ll use one console utility called: debug().

But before, we need to talk about one important implementation detail of Chromium: site isolation.

Site Isolation and process re-use

Site Isolation is a pretty big security feature of Chromium, which became even more important in the post-Spectre world. The Chromium project provides a really good summary of the security benefits and trade-offs on its official website.

The only thing that matters for us in the context of this blog post is the fact that Chromium runs different Sites in different processes. But what is also important is that Chromium might run two different origins of the same Site in the same process. In other words: it may re-use the process for two different origins.

To prove that it happens, consider the following scenario:

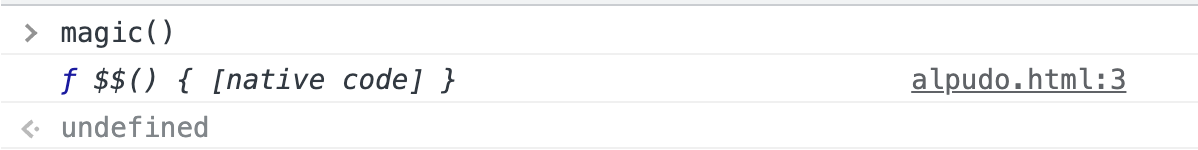

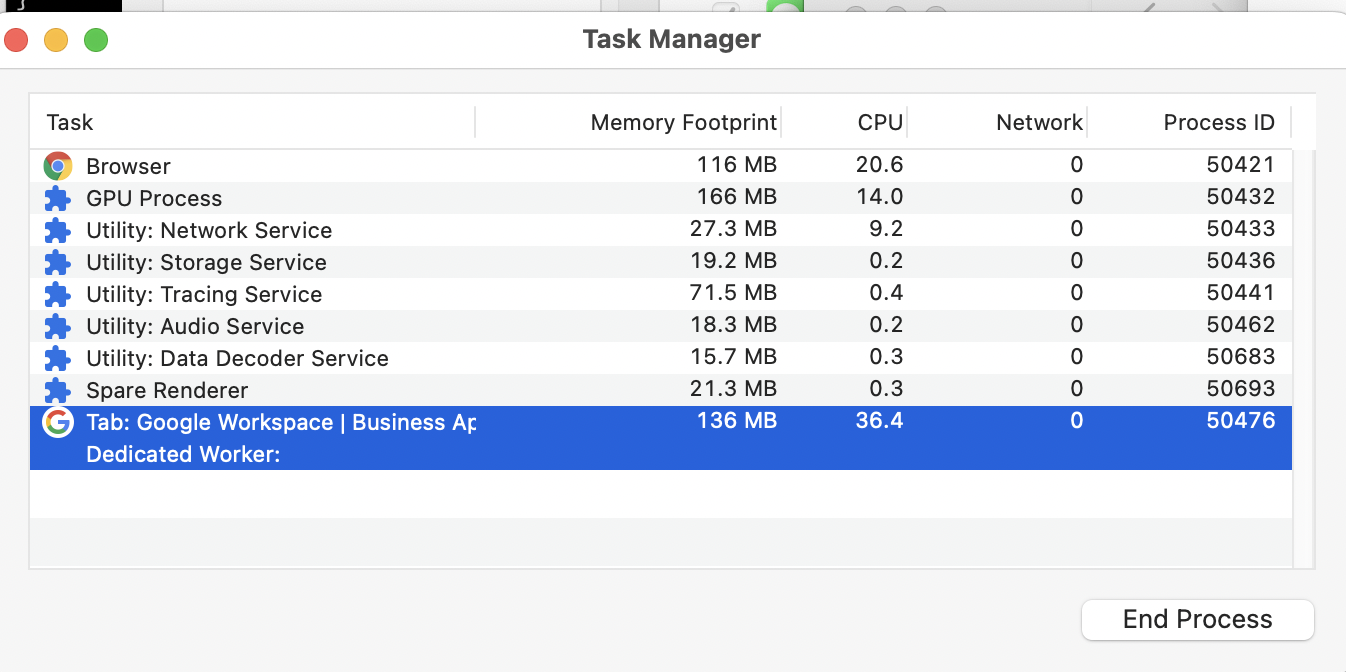

- Open the Task Manager in Chrome.

- Open

https://support.google.comand take note of the Process ID (in the example below, the ID is50476).

- Go to the address bar and change the address to

https://workpace.google.com. - Notice that the Process ID is still exactly the same (for me, still

50476).

So the Process ID hasn’t changed, which implies that it is still the same process, even though it is serving a different origin. This will come in useful in just a bit.

Meet debug()

debug() is a really useful console utility in Chromium; I use it in bug hunting or penetration testing all the time (but maybe that’s a topic for a separate blog post).

The basic idea is that with debug(), you can set a breakpoint whenever a function (given as the first argument to the function) is called. The second argument to debug() is optional, and this is a string of JavaScript code with a condition; the breakpoint will be hit only if it returns a truthy value.

The following snippet explains the usage of debug():

function foobar(arg) {

/* ... */

}

// Example #1

debug(foobar); // will hit a breakpoint any time `foobar()` is called

// Example #2

debug(foobar, 'arguments[0] === "test"'); // will hit a breakpoint only if the first argument is equal to "test"What is especially cool with debug() is that you can even set breakpoints on built-in functions! Want to break on document.appendChild? debug() comes with a rescue:

debug(document.appendChild); // will break any time document.appendChild is calledInterestingly, you can abuse the second argument of debug() to call some other function on function call without hitting the breakpoint. For instance: console.log() returns undefined, so it will make the breakpoint not being hit, while still logging the data.

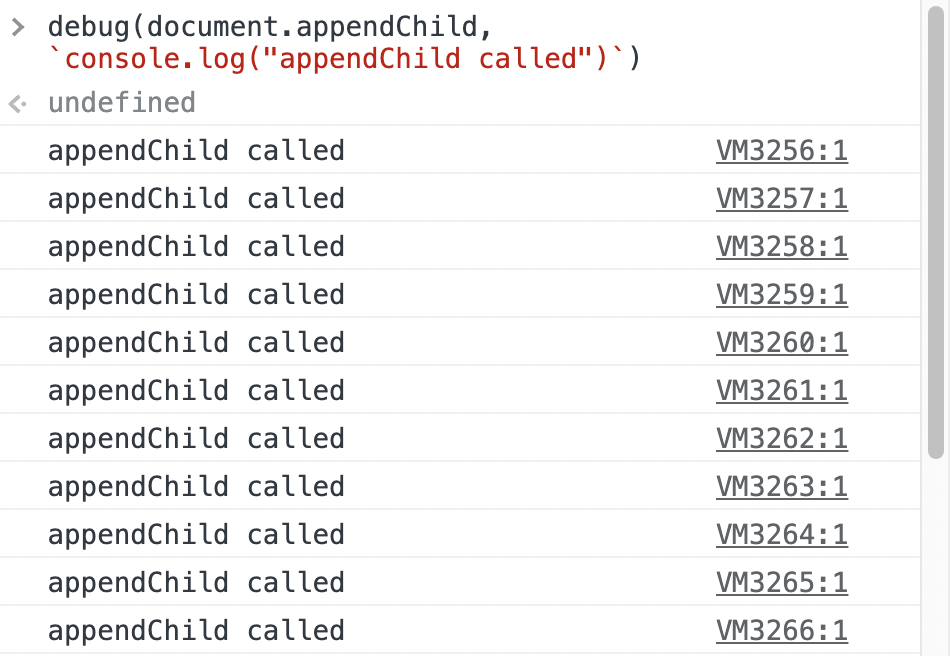

As an example, visit www.google.com, and enter the following code in the console:

debug(document.appendChild, `console.log("appendChild called")`);Afterward, enter something in the search bar and you’ll notice tons of "appendChild called" messages in the console.

And now comes the tricky part (also known as the buggy part). Just try to refresh the page. And surprise: "appendChild called" messages do appear again! You can watch that in the video below.

I found this quite unexpected. I had assumed that refreshing the page would kill all my breakpoints; that the process will be in a “clean state”. But that’s not the case.

It’s also not the end of the story. Remember when we verified that Chromium can re-use a process if you stay on the same Site, even if you are in a different origin? It turns out that if you set a breakpoint on one origin, and then move to another one (but still within the same process), the breakpoint is re-used!

This is proven in the video below, which shows that I enter some code on www.google.com, and after redirecting to developers.google.com, it still executes.

This has obvious security consequences: you can enter a code on one origin, and the code then executes on another origin. So this is a Same Origin Policy bypass although it is limited only to a single Site.

“Google Roulette”

Now it’s time to move on to the title of this post, which is “Google Roulette”. This is my idea of showcasing the security issue related to this bug. Suppose the attacker has an XSS on developers.google.com, and the page asks you to go to the console and enter a single command: magic. All of a sudden, you are now XSS-ed on various Google domains! Watch it below.

And here’s the code:

function xss() {

if (window.__alerted__) return false;

// I could use more origins but you get the idea

const ORIGINS = [

"https://developers.google.com",

"https://www.google.com",

"https://support.google.com",

"https://careers.google.com",

"https://images.google.com",

"https://workspace.google.com",

"https://firebase.google.com",

];

alert(`XSS on ${origin}!`);

// Just redirect to the next origin from the list

const nextOrigin = ORIGINS[ORIGINS.indexOf(origin) + 1];

window.__alerted__ = 1;

if (!nextOrigin) return false;

location = nextOrigin;

return false;

}

window.__defineGetter__("magic", () => {

// Call xss() after document.appendChild is called

debug(document.appendChild, `(${xss})()`);

location.reload();

});Conclusion

In this post, I described an unfixed bug in Google Chrome that allows bypassing the Same Origin Policy within a single Site. The core idea is that within the DevTools console, breakpoints set via debug() function can leak into different origins as long as you stay within a single Site.

While the effects are obviously serious, the fact that you need to enter some code in DevTools makes it a vulnerability that would be difficult to exploit in the wild. You can even claim that it is in the self-XSS territory (although there is escalation to different origins so I don’t fully agree with that point of view).

When researching this issue I thought about making this issue more likely to be exploited… and ultimately failed. But I’m still listing them below; maybe those ideas will be useful to you, and you’ll find a way to exploit them with less user interaction. So here are the ideas:

- There might be functions that are run automatically when opening DevTools. Maybe you can hook into them, and the evil code will also run automatically?

- By default, DevTools console has an eager evaluation. Maybe there is a way to trick it into calling a function with side effects (so that the victim won’t have to press “Return”).

- Check whether this issue can be somehow abused via extensions.