Yet Another Google Caja bypasses hat-trick

One and a half year ago, I wrote a blog post about my three XSS-es found in Google Docs and Google Developers thanks to Google Caja bypasses. In this year, I had a short look at Caja again and it resulted in three another bypasses, not related to the previous ones. So let’s have a look at them!

What is Caja?

According to the official documentation, Google Caja “is a tool for making third party HTML, CSS and JavaScript safe to embed in your website.” Basically it means that you can take some JavaScript code from the user and run it within the context of your website and be sure that the third-party code won’t be able to access sensitive date on your origin, e.g. users cannot access the original DOM tree.

On caja.appspot.com (Caja Playground) you can test Caja by inputting some HTML code, clicking “Cajole” and seeing how your code behaves after being rewritten.

When we try to use the most classic XSS vector in Caja Playground (that is: <script>alert(1)</script>), in the response we should see an alert.

Please note that even though we tried the simple alert(1), what we actually see alerted is “Untrusted code says: 1”. This happens because in Caja Playground the original, native alert function is overloaded by Caja to prepend the “Untrusted code says:” text. This is very useful for testing, since if the “Untrusted code says” part is missing, then we are sure that we escaped the Caja’s sandbox and called the original function.

JavaScript and eval

In JavaScript there are many possible ways to execute code by passing a string to a function, the most common one being eval. However in terms of breaking sandboxes, usually Function constructor is more useful. We can get the reference to the constructor either via global object or via constructor field of any function.

A feature of Function constructor that makes it valuable in breaking sandboxes is the fact that the code is executed in the global scope.

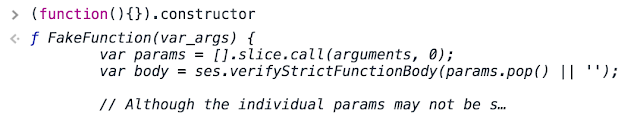

So can we use it in breaking Caja? Of course not :) When we try to access the constructor within Caja, we find out that it is overloaded with FakeFunction.

In FakeFunction Caja verifies the function body and makes sure that the proper sandboxing is in place. Interestingly, the generator function constructor is also overloaded even though Caja parses JS according to ECMAScript 5.

I once tried to somehow escape the function verification patterns used in FakeFunction and FakeGeneratorFunction but failed. Well…

Async Functions

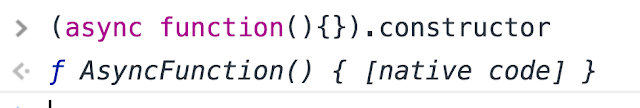

However, the other day I was browsing MDN, and noticed that async functions - one of the coolest features recently introduced in JavaScript - have a new constructor!

Keeping in mind that Caja hasn’t been actively developed for some time now, I was pretty sure that this would make it possible to bypass the sandbox. I went to Caja Playground and issued the following code:

<script>

<!--

(async function () {}.constructor("alert(1)")());

</script>

(to find out why I needed the empty comment the line before (<!--), check my previous article about Caja bypasses; in short - it is needed to make sure we’re not getting syntax errors from Caja’s JS parser)

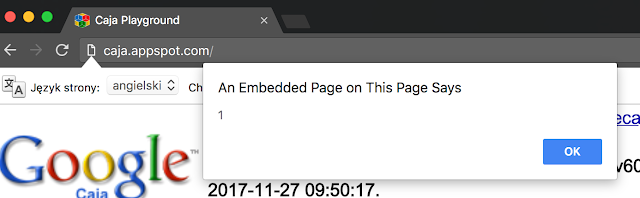

I “cajoled” the code and…

That’s it - an alert not prepended with “Untrusted code says:“! Meaning the sandbox is bypassed :)

Going through ECMAScript’s new features

A few days after submitting the previous bug, I thought that maybe I should keep the ball rolling and check other new, shiny ECMAScript features to bypass Caja. I checked the famous Kangax Compatibility Table and had a look at all features listed there. The one that especially caught my attention was async iterator. That’s right - there’s also a new constructor for that.

So the following would also bypass Caja:

<script>

<!--

(async function\*(){})\['constructor'\]('alert(1)')().next();

</script>

I reported this to Google and was pretty sure they would say that both bypasses are pretty similar and have the same root cause. But, to my surprise, I was actually awarded a second bounty for that. Thank you, Google!

ECMAScript’s new features again

I couldn’t find any other features that could be abused to bypass Caja, so I thought that my luck with this kind of bypasses had already finished. How wrong was I!

I didn’t realize that Kangax’s Table didn’t include all ECMAScript proposals. And the feature that completely slipped my mind was dynamic import. Thanks to dynamic import, we can use import() just as it would be a function in code that needn’t be of type=“module”, for example:

<script>

// Import script based on username

import(`http://example.com/user-scripts/${username}`);

</script>It didn’t really seem probable that Caja would somehow be able to influence dynamic imports so I went up with the code:

<script>

<!--

import("data:application/javascript,alert(1)");

</script>

And that constitutes the third Caja bypass :)

You can watch all the bypasses in the video:

Summary

Thanks to new features of ECMAScript, I could find three ways to bypass Caja sandbox.

Caja released an official security advisory, in which they describe the fix: “in order to prevent future vulnerabilities of this form, we have switched to having SES and Caja always parse and rewrite the input JS, to guarantee that the input is within the correctly-understood subset of the language.”

Timeline

- 28.08.2017 – Reported the async function bypass,

- 28.08.2017 – “Nice catch”,

- 02.09.2017 – Reported the async generator bypass,

- 04.09.2017 – “Nice catch”,

- 19.09.2017 – Got reward for the two bugs,

- 29.09.2017 – Reported the dynamic import bypass,

- 02.10.2017 – “Nice catch”,

- 10.10.2017 – Got reward for dynamic imports,

- 19.11.2017 – Asked Google when I can expect the bug to be fixed,

- 27.11.2017 – Google responded that the bugs have been already fixed but not deployed. And deployed the new version the same day.

- 30.11.2017 – Blog post.